UPDATE: The person involved spoke with me in person, and so I have decided to remove her name from this post. Thank you also for the support I have received, it warms my heart.

****

Just got back home (Kitigan Zibi) after a 65 hour fast. For approximately 10 years my fasting ceremonies have been taking place within the perimeters of my home community. Before that time, I went to the Temagami area and also to Thunder Bay. I fast twice a year, once in the spring during the time of the Flower Moon (May), the other in autumn, during the time of the Moon of Falling Leaves (October). I have been doing so faithfully since five years after my sobriety began over 30 years ago. At the beginning I fasted for 4 days and nights, no food, no water. I never once quit. Spirit at the fasting circle has always been kind and generous to me. I have learned so much and I believe each ceremony has made me a better man of the Algonquin Nation. Part of my ceremony is and always will be for the revival of the original spiritual beliefs of this country. Indigenous spirituality is real. It is strong and beautiful and needs to be brought back to those of us who recognize it as something spiritually special that Creator gave solely to us, the original inhabitants of these magnificent and resource-rich lands. Spirituality? It is water! Try filling a glass with loonies and pouring them down your throat, it won’t quench your thirst.

On the afternoon of Wednesday, October 24, I left the serenity, solitude and healing of the fasting circle and arrived into my home feeling very much at peace with the world and spiritually well. Then a call comes in via my cell phone notifying me that a young Algonquin woman is attacking me on Facebook. This person advocates for Windmill Development Group, the developer hell-bent on building condos on a sacred site located in the heart of Algonquin Anishinabe territory. The screenshot of some of her comments is below (with her name removed).

At no surprise to myself, I discover that she does not recognize me as an “elder.” This is quite OK with me. I never set out in life hoping that people like her would embrace me as an “elder.” I don’t even like the word “elder.” To me, it is a word too closely connected to organized religion. I prefer to be known as a human rights activist, and to those who wish, as a spiritual advisor and helper. That being said, there are folks in my community of Kitigan Zibi (KZ) who do refer to me as an elder and I’m at peace with it. I’ve been asked a couple of times to help out as an elder with KZ’s Pow Wow. On one occasion I accepted. I’ve helped out at the school as an elder (after a tragic event had taken place) and was called in to help when the Restorative Justice program was revived. Obviously, there are many people in my home community who do regard me as an elder.

I do not know this person. All I know with 100% certainty is that I have not harmed her in any way. She has no call to attack me as she has. Her comments about me on Facebook were extremely hurtful. It was heartbreaking for me to feel under attack by a young Algonquin woman. If she wants, I’d be happy to sit with her and tell her the many reasons why I do not object to folks recognizing me as a spiritual advisor and she can tell me the reasons why she believes I am not. Whoever it was who put those hurtful words into her mouth tricked her. Why?

This young woman also attacked Jane Ann Chartrand on Facebook. Jane is an Anishinabe Kwe and grandmother beyond 70 years of age. Her comments about Jane are vile and shocking, and could be described as a violent attack on Jane’s character. (Whatever happened to ending violence against our women?) Do the ugly words cast at Jane Chartrand by Josée come from the teachings of her “elders”? Or are they the words of someone who is slowly heading to a place where souls are bought and bartered for? Young Anishinabe women attacking old Anishinabe citizens is not our way of life. When such nonsense becomes commonplace, it will mean that the Anishinabe Nation no longer exists.

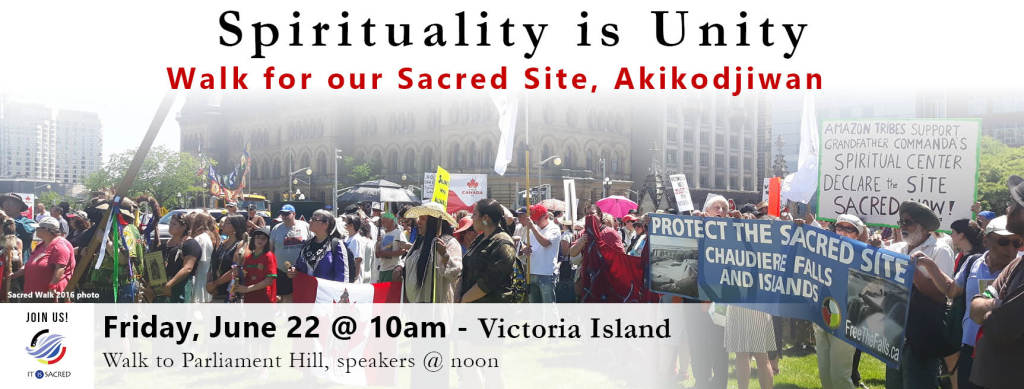

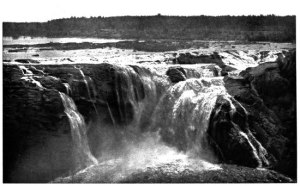

I help out however I can to return Akikodjiwan (AKA Chaudière Falls and the nearby islands) to the People. It is a sacred place, and always was to the Algonquin Anishinabe of past times. I’ll continue to do what I can to preserve it and will do so without expecting monetary compensation for the countless hours I have invested in this very worthy and honourable cause. In my eyes the Free the Falls group are solid activists whom I welcome by my side in the struggle to save sacred Akikodjiwan. So what if many of them are white people! Has it become a sin to be a white activist? She blasted the Free the Falls activists for being “white,” yet the people at Windmill who want to build condos on our sacred site are, yeah, you guessed it, white people.

However all this plays out in the end, I will not hold any grudges nor condemn Algonquins who fought on the side of the developer for condos to be built on our sacred land. Their beliefs are what they are and I recognize their human right to defend them. I expect the other side to do likewise for me.

By the way, I don’t have a clue as to what an “Algonquin Practitioner” is.

Over 20 years ago, Phil Jenkins wrote An Acre of Time. He extensively researched the history of the Lebreton Flats in Ottawa, near Akikodjiwan (Chaudière). Below is a quote from the book regarding the continued presence of the Algonquin Anishinabe people in the National Capital region. This originally appeared as a comment on January 15th on my blog post, Algonquin Land. It is posted here with Jenkins’ permission.

South Wind

Excerpt from “An Acre of Time”

Because of a petition Constant made to the British department of Indian Affairs in the February of 1830, when he was 44, we know where those hunting grounds were. In the document Constant says,

“That after several years the hunt has more and more diminished with the destruction and the distancing of the beaver and of game. The only means of subsistence of the supplicant whose hunting grounds, situated to the South of the Ottawa at the top of the Rideau, are almost all ruined by the incursions that were made and the numerous settlements that now run along them.”

The expanse of Constant’s family territory can only be guessed at, but the average Algonquin grounds was 100 square miles, or an area ten miles by ten. The “incursions” that Constant mentioned in his petition were the first stirrings of settlement, stirrings that would divide, sub-divide and eventually become Bytown, then Ottawa, the capital city of the British invasion. Constant and his family were to be replaced, in six generations, by half a million people.

Within a couple of months of his petition, Constant got a form letter. It was a fancy-looking document dressed up as a certificate, flourishes and filigreed edges, designed to impress the receiver. It came from Sir James Kempt who was, as it said at the top of the paper, “Captain General and Governor-in-Chief in and over the provinces of Lower and Upper Canada,” as well as of other glories. Sir James wanted Constant to know that he was “reposing especial trust and confidence in your courage and good conduct, and in your zealous and faithful attachment to His Britannic Majesty King George.”

Four years after Constant, together with a Nippissing chief, went to visit James Hughes, an Indian Affairs agent in Montreal. Hughes later reported the meeting to his employers, giving his take on what the two chiefs had on their minds. An edited version of his letter reads,

“Old Constant Pinaisais [French spelling] was here a few days ago. He brought a map made a few years past. These lands on the borders of the Ottawa are now almost all settled.

They however have marked out a lot above the Grand Calumet Portage some distance above the last settlements. They would wish to have a township or a seignorie given to them there, before these lands are granted.

It is on the south side [of the river]. There is an island before it which they would also like to have, to make hay thereon and place their cattle in summer. They say they have no encouragement to work on pieces of land that are in manner only lent to them, whereas were they masters of a certain tract that they could call their own, they would be happy and industrious. They would have it in their power to make better hunts – find more deer and catch plenty of fish.

The history of the British theft of the Algonquin way of living is right there in those few words. No-one goes through life without feeling great change, but Constant Penency found himself pushed over the edge of an era. He was born a free hunter’s son, and by the age of 50 he was asking men born in another world for the right to relinquish any claim on his birthland, and to become a sharecropper and part-time trapper far away from their incursions.